Writing Likeable Characters . . . Or Not

Tag Archives: Writing

Brief Notes on Movies Vol. 1 No. 2

Sometimes Kalene and I spend so long trying to decide on which movie to watch that we run out of time for actual viewing. To combat this, I sought out several online lists of best/worst movies in different genres.

This comes from from a Rotten Tomatoes list of the best slasher films.

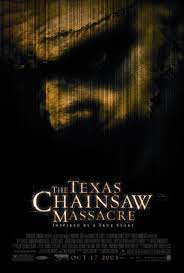

#94: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)

- Director: Marcus Nispel

- Starring: Jessica Biel, Jonathan Tucker, Andrew Bryniarski

- Had I seen it before? No, because like a lot of critics, I looked on this movie as unnecessary. Why remake a good movie without updating anything? It just seemed repetitive.

- Should it be on such a list? You know what? I’m okay with it. Yes, it remakes the original without doing something new to justify its existence, but the acting is a lot better than you often see in slasher films. The new death house is creepy, more in an typical-house-of-horrors way than in the original “inbred cannibal hicks with terrible taste in decorating” set design. Like the original, it feels brutal without actually showing all that much gore. The filmmakers miss the subtler (!!) aspects of Leatherface’s masks, but this doesn’t hurt much. Jessica Biel also isn’t required to scream nonstop for half an hour, which cuts down on the teeth-grating tension of the original, but I’m not complaining. One TCM using that many screams is fine. So were the critics right? Is this movie unnecessary? Yep, but it exists anyway, and unless you’re simply offended that anyone would remake the original, this one isn’t a bad watch.

There will be more installments in the future. Join me, won’t you?

In the meantime, buy my books. All the cool kids are doing it.

Got comments, questions, or complaints? Email me.

ICYMI: Book Trailers!

Thanks to Megan Edwards and the great folks at Imbrifex Books, you can now view the book trailers for Comanche, Lord of Order, and my forthcoming young adult novel Freaks. Enjoy and share! (Oh, and buy the books. Support independent authors and presses!)

One Man’s Opinion–FanFic

Last semester, a student asked me how I felt about fan fiction. I suppose it counted as one of those “don’t ask the question if you don’t want the answer” situations.

For me, fan fiction can be a good way to keep your creative juices flowing. It can be a way for burgeoning writers to find a (hopefully) supportive community. It can be a way for fans who are passionate about a given book/film/show/etc. to join a creative conversation about the text in question. There is even a chance, however miniscule, that it can provide exposure, which in turn might lead to offers, an agent, a contract, etc.

But.

While writing (or, for that matter, reading) fan fiction can be a fun creative exercise, it should not be the primary vehicle for a serious writer’s creativity.

I don’t mean “serious” in any kind of elitist or dismissive way. I’m seriously invested in pop culture and believe that a good horror movie or graphic novel or sci-fi TV show can be just as valuable and engaging as the most serious literary fiction. “Serious writer,” though, suggests a person who envisions writing as an artistic pursuit and/or a career. And, unless you can score a spot in the writer’s room of your favorite TV show or land a solicitation to write the next sequel, what you can do with the text will always be limited.

One reason is, of course, the violation of trademarks and copyrights. You can write all the screenplays you want for the second season of FIREFLY or a sequel to ‘SALEM’S LOT, but unless you have written permission to use those characters, nobody’s going to option, buy, or publish your work.

Another reason is that artists in general take risks.

Writing for yourself and your friends as a fun exercise can be harmless enough and, as stated above, it can help keep your creative edge well-honed. But “writing for yourself and your friends” isn’t the same as creating original works to share with the world. Generally speaking, creating new worlds and characters is harder than imagining further adventures for something already established. When talking to some writers who really want to pursue their art but ONLY on websites and forums dedicated to fan fiction, I often find that they lack the confidence to try and create something from scratch. To these writers, it feels safer to work with a world that has already found some degree of success, whether in critical or popular realms.

One aspect of art that young writers need to understand: you can’t be afraid to fail. Most people fail at different points in their career. Not everything you create will be wildly popular and/or critically acclaimed.

That doesn’t mean your work is without merit. Tastes vary, and today’s successful novel might be forgotten tomorrow, while an obscure, ignored, and/or critically lambasted book from today might be lauded as great sometime in the future. Look at Herman Melville, who enjoyed some initial popularity, then drew the ire of critics and the indifference of audiences to the point that he died more or less broke and obscure. Now we study him as one of the great voices of the American nineteenth century. Or take the poets who were popular in that same century. They don’t get nearly as much attention now as two poets who were truly ahead of their time—Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

What all that means is that “failure” and “success” are relative and subjective. You can measure success by your brave attempts to make your own art, or by whether you get published (regardless of sales/acclaim), or by sales, or by acclaim, or by how good it feels to take the stories burning inside you and put them on the page, whether or not they light a similar fire in anyone else. Or you might measure success by some other metric entirely.

The point is that only you can really know how successful your writing is TO YOU. To allow anyone else to determine how much your work means in your own heart is to give them power over your deepest self.

As a writer, you do the best you can in the time you have, and you put your work out there, and then you move on. It will live and breathe on its own.

What does this have to do with fan fiction? Again, when people sometimes ask me about fan fiction, I often get the feeling they want me to legitimize their choice, to tell them that writing fanfic and ONLY fanfic is a legitimate way of being recognized as a writer. That it’s okay to stay on that same forum, writing for the same people, about the same texts all your life.

If you’re doing it because it’s truly where you tap meaning and satisfaction in your work, fine. Neither I nor anyone else has the right to tell you what you’re doing is wrong. You will have to realize that the world of the arts and broader audiences almost certainly won’t seek your work out or disseminate it or pay you for it or throw accolades your way. But if you are willing to pay that price, then huzzah.

HOWEVER.

If you’re only staying on that forum out of fear—of success, of failure, of criticism, etc.—I would encourage you to reach. Go beyond what’s comfortable. Take risks. I am here to tell you from experience that good reviews and money and all that stuff feel good, and that mediocre or bad reviews, jerks @ing you on Twitter and IG, and so forth are survivable if you believe in yourself. Fear is one great nemesis of art. Don’t give in to it.

And, again, only you can define what “success” and “my art” mean to you.

When people ask about fanfic, it therefore doesn’t really matter. But if they still want my take, I tell them that it shouldn’t be your primary means of expression if you truly want to be a “serious writer,” which isn’t to say that writing fanfic is useless or worthy of my derision.

Bottom line: If you want to make expanding existing worlds your primary creative pursuit, you could try to break into the worlds of screenwriting or comics. You’ll have to know going in, though, that those fields are just as competitive as any other in the arts/entertainment world. If you can do it, that would “legitimize” your use of other people’s work.

Otherwise, I advise you to spend at least part of your time creating your own worlds. You never know what will happen.

That’s one man’s opinion, which you can take or leave as you like.

New Fiction Published

My short story, “Everyone Here Comes from Somewhere Else,” is now live at THE COURTSHIP OF WINDS. Please check it out. And if you don’t like me enough to read it, at least click on it and give the journal a hit, mmmmkay?

New Fiction Acceptance

Thanks to the small online literary mag THE COURTSHIP OF WINDS for accepting my short story, “Everyone Here Comes from Somewhere Else.” This is one of those stories that is kind of a hard sell, and I’m very grateful someone appreciates it. And thanks, as always, to God, Kalene, my kids, my friends, and my readers.

Dispatches from Minneapolis and other Points Abroad, #AWP15

NOTE: What follows is a hastily composed, mostly unedited account of this year’s AWP from my perspective. I don’t claim that it’s representative of anyone else’s experience.

Day 1

Ah, travel—asleep at 1 am Las Vegas time (PDT), then startled out of a now-forgotten dream at 4:30 am, an hour so ludicrous and detrimental to sanity that it should not even exist. Even milkmen and grumpy old cigar-smoking guys running newsstands would shake their heads and groan. My wife Kalene got up first and showered. I fell back asleep. Half an hour later, she woke me up to tell me that I could sleep another extra hour because we had gotten a text from Delta Airlines. Our flight was delayed an hour and a half. I had never been grateful for a late flight before, and for a moment, I flashed back to last year’s AWP trip, when my flight to Long Beach got delayed so long that I missed my connection and had to head for Seattle the next morning. But once I realized the implications of what Kalene was saying, though, I nestled deep into the covers and crashed until she dragged me out at 6 am.

The fingers of my right hand and the muscles in my forearm have ached all day because I spent over thirty minutes last night setting up our DVR for the next week. Our Cox remote only recognizes that you’ve pushed a button after you’ve done so four or five times, so multiply that by recording five to ten shows a night for the next week, and you can probably understand why I’m sore. (“Why doesn’t he just set up a series recording?” you might wonder. It’s because our multi-room DVRs sometimes just decide that they don’t feel like doing what you’ve told them to do, and often, having little time to watch TV on a given day, I only discover the problem when I’m trying to set up more recordings. The joys of cable! “Why doesn’t he get DirecTV or Dish or something?” you might be asking. It’s because we currently live in an apartment that we rented sight unseen upon accepting employment in Las Vegas. Ours is apparently the one apartment in the building that, for shadowy reasons I only partially understand, is not allowed to have any equipment mounted on the exterior walls. Whee!)

Out the door at 7 am, we dumped on bag of trash in the dumpsters and took Broadbent to Russell to the freeway to Flamingo, cursing every slow driver and flipping off every red light. We arrived at our parking facility, the Silver Se7ens Casino (their spelling; don’t get me started), though to tell you the truth, we picked another place on the Internet but somehow got booked at the one place we knew we wanted to avoid. The last time we parked there, the shuttle rules were so labyrinthine that we missed it and had to pay a cab to take us to the airport, even though we had already paid for parking and the shuttle. When we got back to Vegas, we went to the wrong level of McCarran Airport and missed the shuttle back, so we had to take another cab to Silver Se7ens, meaning we paid for two shuttle rides and never actually even saw the vehicle. Imagine our displeasure at clicking on the “book it” button for off-site parking at a different hotel and then finding that they had dumped us back in Silver Se7ens’ lap anyhow.

We were instructed to park, unload our luggage, go inside to let them know we had arrived, and then park the car. Knowing that we were only going to be there for a minute, we parked behind a shuttle van. My daughter Maya and I unloaded while Kalene ran inside. As soon as we shut the trunk, a burly security guard tooled up in his golf cart and said, “I’m gonna need you to move that car. This area is for shuttle parking.” When I told him that we were there for the shuttle and were simply waiting for our parking assignment, he said, “Oh, okay. So you’ll just be here a minute. That’s good, because the shuttle is gonna be back [looks at his watch, incredulous] any minute now.” Then he looked at me expectantly.

“I knew something like this would happen at this dump,” I said to Maya. I didn’t even bother to ask what the big white bus-looking thing that we had parked behind was, if not a shuttle. I simply loaded all our bags back in the trunk. As I finished, Kalene came out with our parking permit, and we drove around to the garage and up to the fourth level, where we left the car, lugged our bags to an elevator, zoomed down to the casino, fought our way through tourists, and finally arrived back outside, twenty feet from where we started.

The shuttle, whose imminent arrival had so concerned the guard, showed up thirty minutes later. It was a van, much smaller than the bus-like vehicle we had so foolishly thought it might be fine to park behind for five minutes. We piled inside and took the ten-minute trip to Departures, where, as I disembarked, I was promptly almost flattened by a bus being driven by, it seemed, Sandra Bullock and Keanu Reeves.

Inside the airport, there was virtually no line at the bag-check counter or security, and no one decided that today would be a good day to pull the Rileys out of line and wand them and pick at their laptops and stare suspiciously at their phone chargers. We made it to our gate in plenty of time.

For breakfast, a big slice of pizza from the airport’s Metro outpost. Though our flight was delayed, the gate personnel were on duty already, and they worked their magic so that we could all sit together. When we booked the flight, we had chosen seats next to each other, but of course that didn’t take, and they had spread us all over the plane, me in the fourteenth row and Kalene and Maya in different sections somewhere in the twenties. Now we all boarded together, sat together, and fell asleep together as soon as the plane cleared the runway.

Twenty minutes later, I woke up. My memories from Delta Flight 1851, with service from Las Vegas to Minneapolis:

- When asked for my beverage choice, I picked coffee, which I never do on flights because it sometimes hits my bowels and bladder like a sledgehammer, sending me scurrying for the insidious inventions known as airplane lavatories, so small and cramped and loud that it simulates the effects of riding in a coffin to one’s own funeral via a major freeway. This cup was good to me, though. I got up only once afterward.

- However, we were flying coach, and when the airline personnel moved our seats, they put Kalene and Maya in my row, near the front of the plane, so the coach lavatory was approximately a quarter-mile away from us, the way often impeded by the refreshment carts, which are engineered to fit (barely) in the tiny, cramped aisle in much the same way that a drawer fits into a cabinet. Of course, we could have just headed up to the much-closer business-class potty, but airplanes are such obvious symbols of the American class system that I’m always half afraid that some sonorous claxon is going to sound as soon as I pass the curtain, that some air marshal will tackle me and cuff me and then lecture the rest of the coach-riding riffraff on the perils of not knowing one’s place. So, yeah, I waited on the carts to move.

- Speaking of class—for those who have never been on an airplane, you have more room in business class, and a flight attendant dedicated to serving the ten or twelve of you on that side of the curtain. When I have flown business class, I have known the exquisite sensation of stretching my legs all the way out without kicking anyone or banging my shin on the underside of a seat, taking off an inch of skin. I have had someone take my coat and hang it up for me. I have had attendants call me by name. I have been asked for my beverage preference and gotten whatever I wanted without extra cost. Contrast that with coach, where you are crammed in two or three to each side of the aisle in a configuration that a sardine would dismiss as too restrictive. You don’t get premium drinks unless you pay for them, credit cards only; you get a small plastic cup of juice or soda, perhaps a cup of coffee. Today, I watched business-class customers be served full breakfasts in real dishes and on actual platters. Then I watched those who had upgraded to a “comfort seat” be served from a fruit-and-muffin basket. Then it was our turn. I got a cup of coffee in a small Starbucks cup and two ginger snaps. Two. Ginger. Snaps. Don’t tell me there’s no American underclass.

- Across from me, some guy spent the entire flight frantically rearranging everything on his computer. We weren’t close enough for me to see what he was doing, so I didn’t feel like I was snooping as I watched him open multiple windows and cut parts of a document out and paste that part into an email and send it and then go to other documents and cut out parts of them and paste them into different emails and send them and on and on, ceaselessly, for three hours. He looked like one of those computer experts you see in action films, the ones who create a sophisticated virus and hack a major secured network in thirty seconds with nary a typo. Maybe those people really do exist, though from the images I spotted, this guy appeared to work for an auto manufacturer.

- On the way, I read the first chapter of a novel that won the Pulitzer for fiction and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Within a page and a half, I found what appeared to be two misplaced modifiers. Now let me assure you that the chapter was mostly excellent, in terms of grounding and characterization, deft use of exposition a bit at a time, and so forth. But those modifiers haunted me. I couldn’t help but wonder if they would have been enough to get most people rejected, regardless of their manuscript’s strengths, and that led me to a long, dark reflection on the entire publishing industry and how random things sometimes seem.

- People sleep ugly on planes—necks cranked hard to one side, giving them the appearance of having been throttled to death; mouths open wide enough for you to throw things in there; strangers’ heads falling onto other people’s shoulders. It makes me wonder what I looked like during the first twenty minutes of the flight.

Arrival in Minnesota at approximately 3:20 CST—naturally, we deplaned at a gate so desolate that we needed to take a taxi just to reach the taxi stand. Without this option, we hoofed it for God only knows how long, barely making it to baggage claim before somebody hauled our luggage away.

Observation—on its outskirts, Minneapolis in April looks much like Mississippi in January. Downtown seems shiny and clean, even when it’s overrun by writers…and today, it wasn’t nearly as overrun as it’s going to get.

Our room in the Millennium Hotel is nice but small. The bathroom door is either so modern or so old school that it doesn’t have a lock; it slides shut, and then you have to trust your roomies not to burst in on you. It’s got two double beds, meaning that Maya gets one to herself, while Kalene and I have to adjust to not having our queen-sized mattress. I expect some elbowing to occur later. The hotel has no distilled water for my cPap machine, and there is apparently no pharmacy or grocery outlet within walking distance, so I am faced with the rather silly task of paying for a taxi in order to procure a gallon of water. That, or not, you know, breathe while I sleep.

The registration process was a breeze this year but for the walk. From the hotel to the convention center to the specific part where registration occurs is about as far as the hike from our airport gate to the taxies. I’ve gotten my exercise for today.

Dinner at the hotel bar—Scottish salmon with mixed veggies, fingerling potatoes, and arugula. It was an excellent dish. To wash it down, I tried a local brew called a Surly Furious. If there were ever a beer made to fit my personality, it’s that one. As I joked on Twitter, it even has the bitter aftertaste.

We retired to the room by 6:30 pm CST, where I have thrown this dispatch together through the fog of exhaustion that makes any grading or work on a manuscript unlikely. Perhaps tomorrow, after a few sessions but before Karen Russell’s keynote speech.

It seems to me that writers gather together like this, in spite of snafus and grumpy airport personnel and the bone-deep exhaustion that sets in before you even get your lanyard, because, in part, writing is a solitary, lonely activity that much of the world can’t wait to dismiss. From people who get up in the morning and make the effort to insult you on Twitter to the comments sections of website articles you’ve written to the odd guy who shows up at your signing with blood in his eye, the average artist in any medium must first struggle against his/her own sense of inadequacy and a lack of funding, against a government that devalues what keeps us human, against hatred and small-minded sniping and careless words. Here, at AWP and other events like it, we can come together, support each other, reach out and make contact.

Yet these places also exacerbate one’s sense of never having met one’s goals. There is a comparative element that is at times inescapable—“look how little I’ve done compared to so and so.” There is, if your specific friends don’t show up, the lack of the very community that you’ve come to seek.

In a few weeks’ time, we’ll be able to look back and measure the effects of this year’s conference on our self-images, our contacts, our careers, our art. Now, we’re busy living it. This was my first day.

Given world enough and time, more tomorrow.

Follow me on Twitter: @brettwrites.

Email me: brett@officialbrettriley.com

Visit my website: https://officialbrettriley.com/

Check out my Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/BrettRileyAuthor?ref=aymt_homepage_panel

Screenplay Annoucement

For those who haven’t heard, I adapted my short story “An Element of Blank” (first published in The Evansville Review) into a feature-length screenplay entitled Candy’s First Kiss. Last week, I received word that this manuscript won the horror/sci-fi grand prize at the New York Screenplay Contest.

You can find a list of all 2014 winners here.

Agents, studios, and others interested in optioning this screenplay can contact me at my email address, brett@officialbrettriley.com.

#MyWritingProcess #BlogTour

“My Writing Process” Blog Tour

My friend C.D. Mitchell tagged me as part of the Blog Tour. I always appreciate the opportunity to publicize my work and that of other writers, so for whatever it’s worth, this is my contribution.

What am I working on these days?

I’ve got a lot of irons in the fire. Due to spending several years in graduate school without much time to submit my work, I’ve got a pretty good backlog of text that I’m shopping. My somewhat-experimental novel-in-stories The Subtle Dance of Impulse and Light dropped about this time last year. You can find it on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other fine online retailers. I’m spreading the word about it as much as I can.

I’m currently submitting two works to independent publishers. One is Mulvaney House, another somewhat-experimental novel. It traces the (d)evolution of a single house in southeast Arkansas from the late 19th through the early 21st centuries. It is first inhabited by ill-fated Irish immigrants; later, its ownership passes to a disillusioned World War I veteran. Because that situation does not end well either, the house becomes the local “haunted,” “cursed” place that all the smart kids avoid and that all the cool kids want to explore. In the 1960s, it becomes the setting for a star-crossed interracial romance, and in the early 21st century, three teenagers spend the night there just to prove that they can. Serious carnage ensues.

I’m also submitting my second story collection, tentatively titled Bedtime Stories for Insomniacs. Most of the stories therein have been published. In terms of subject matter, it’s a pretty eclectic book. There’s a serial killer story, a couple of tales that make use of mythological creatures, some gritty realism, and some humor.

I’ve gotten some kind words about the projects, but whether they will ever see the light of day is anyone’s guess.

Oh, you thought I was through? Not yet—I’m also shopping The Dead House, a literary ghost story. It’s a novel-length work set in central Texas, though many of the characters are from south Louisiana. The book is a supernatural thriller detective fish-out-of-water story. I’ve gotten a few nibbles from literary agents; I’m hoping to land one soon.

In terms of new work, I’m currently drafting a post-apocalyptic novel set in the South. I’m also three stories into a new cycle that will, I hope, become a book one day.

I recently submitted a screenplay that I adapted from one of my published stories. As I have no contacts in Hollywood, I don’t expect it to go anywhere, but hey, they have to option somebody’s script, right?

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I’ve always thought that this kind of question is best answered by critics and scholars, not writers. I just tell stories. Some editors have compared various stories I’ve written to writers as diverse as Jack Kerouac, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Elmore Leonard, and Ernest Hemingway. (I’m not egotistical enough to say that I agree, but I really appreciated their saying it.) I think a couple of my stories read like they were written by the love child of Stephen King and Cormac McCarthy. What all this means, I think, is that you can get a pretty good read on my basic format and style, but the content and how I employ that style may vary widely from piece to piece. I try not to write the same thing twice, and if I do delve into an area that I’ve visited before, I try to change perspectives, or voices, or tones, or something that will make the work seem a little fresher.

I don’t know what my genre is, other than “literary,” so no matter what similarities and differences a given reader sees between my work and that of any other serious writer, they’re probably on the right track, even if what they say contradicts somebody else.

Why do I write what I do?

Why does anybody write what they do? I never know what to make of this question. I can only tell you this: I believe that real writers do what they do because they are compelled. You don’t do it for fame. Writing literary fiction for money is a mug’s game. You don’t do it for all the groupies because most of us don’t have any (well, maybe Chuck Palahniuk). You do it because you can’t imagine a life where you don’t do it.

When I don’t get my two daily writing sessions in, I feel incomplete and guilty. When I don’t get at least one session, I feel out of sorts, angry with myself, despairing about the time that has passed. When I don’t write at all, I want to punch somebody, often myself. I have stories and people and dramatic situations in my head. Some of them are funny or sad and sick or cool. Others will probably never really go anywhere. But I have to find out what might work, or I go a little nuts.

As for where I get my ideas, my standard answer is, “A warehouse in Poughkeepsie. Don’t tell anybody.”

Seriously, though, they come to me as I live—sometimes from a bit of conversation I overhear, sometimes from an image I see in life or a movie or a magazine, sometimes from that place deep within my imagination where everything begins with “What if…?”

I write down every idea that I can. I’ve got files of them, ideas for stories and novels and essays and screenplays and comic book series and TV shows. I add to the piles fairly regularly. I don’t know if I’ll ever get to all of them. Some of them probably suck. My job is to write as many of them as I can, and to write them to the best of my ability, and hope that some agent, editor, or publisher will believe in me, in my story. After that, you pray that the piece will find its audience, but you can’t really control that, or the publishing side. You can only write and submit and not give up.

How does my Writing Process work?

I look over my list of ideas and see which one speaks to me at that given moment. Sometimes I’ll outline how I imagine the story will go, but even when I do, I allow for organic and spontaneous growth, when the people in the story do something that I didn’t expect. Most of the time, I just write until I complete the narrative arc. I do a full draft without worrying too much about how well it all holds together.

With my book, I revised extensively, several times. With the novel I’m currently shopping, I revised ten times before I ever submitted it. I’ll tinker with any given story for a couple of drafts until it seems to chug along pretty well.

Then I submit.

In this business, you have to expect rejection unless you’re already a household name. To succeed at any level at all, you have to strike the right combination of talent, learned skill, perseverance, and luck—getting the right piece to the right gatekeeper at the right time. Unless you have personal contacts at an agency or publisher, that’s about all you can do.

I’ll generally send out a piece to a half-dozen places. If nobody takes it, I revise again and find other places to submit. I keep doing that until I find the right home for it or I decide that maybe it isn’t as good as I thought it was. I have yet to self-publish anything, but I’m not above it if the industry never accepts what I truly believe is a story worth telling.

Once someone accepts a piece, I am perfectly willing and able to tinker with it if an editor sees areas that need work. Sometimes I insist on leaving something as is if I feel changing it will fundamentally undercut my integrity as a writer and the story I want to tell, but I pick my battles carefully. I have yet to meet an editor with whom I could not work amicably and productively.

As for my day-to-day process, once I’ve chosen a project of any length or type, I try to write at least twice a day for an hour each time. It isn’t always possible, but I do my best. I tend to work on a couple of projects at once—a potential novel chapter and a story, a story and a screenplay, etc. In grad school, I was forced to multi-task, and I have yet to break the habit completely. Right now, for instance, I’m revising a text and working on a new story. I’ll revise for a session and write for a session. I’ve found that setting time limits, rather than specific word counts, works better for me because of my other time constraints.

I’d like to thank C.D. Mitchell for tagging me.In turn, I am tagging two of my writer friends who occasionally blog, Robin Becker and Sean Hoade.

Robin Becker is a graduate school buddy of mine. She has recently accepted a teaching position at Ole Miss. Her zombie novel, Brains, is available in bookstores and online.

Sean Hoade is a fellow Las Vegan. He has been a prolific self-publisher; his latest work, Deadtown Abbey, is hilarious and weird, and I mean that in the best possible sense. He has recently contracted to write a series of undead-themed books for a traditional publisher, so look for them in the near future., coming to bookstores near you.

#MyWritingProcessBlogTour–C.D. Mitchell

Much like “The Next Big Thing Self-Interview” series that went around on the Internet a while back, the “My Writing Process Blog Tour” asks a writer to answer a series of questions on his/her blog and then tag three other writers. C.D. Mitchell tagged me, so I am re-posting his blog response here. Next week, I’ll post my own. C.D. will publicize my post, and I will tag three other writers who blog. With any luck, they will all respond and publicize my blog entry in kind. I will, in turn, publicize their posts. All backs get scratched.

Without further ado, I give you C.D. Mitchell, author of the short story collections God’s Naked Will and Alligator Stew.

I became a part of this process when Tamara Linse tagged me to follow up on this blog tour. I generally do not participate in such things, but this seemed intriguing, so I tossed my hat in the ring and tagged two fellow writers I admire, Shonell Bacon and Brett Riley to follow me. So here goes!

What am I working on these days?

I am working on a yet untitled novel that will involve smuggling of guns, drugs, and illegals up the Mississippi River and its navigable waterways by riverboat barge. A chapter of the novel, one that deals primarily with President’s Island in Memphis, is scheduled to appear in Memphis Noir sometime this fall. The novel deals with river barge traffic, a largely unregulated means of travel during the early 1990’s. I envision a mix of Mark Twain, Robert Earl Keen and Cormack McCarthy in the final text. My main character has purchased an electric shock therapy machine at a flea market in Mississippi and will eventually use it to collect money on fronted drugs.

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

A recent review of my story collection “Alligator Stew” called the writing “Dirty Realism.” Many of the reviews of my work posted on Goodreads andAmazon.com have observed that I write about situations others shun or ignore. I create real characters faced with desperate situations. I don’t spend six pages describing in flowery language how a dog crosses the road to take a shit in the ditch. That is not to say that sentence construction, word choice and rhythms are not important to me. They are, and they must be important to all writers. But my emphasis is story. Shit happens in the stories I write!

Why do I write what I do?

Because too many others lack the courage to face the reality of life. I write to expose the incredible hopelessness faced by the schizophrenic, by the impoverished, by those cursed with bad luck and misfortune. I write to expose the hypocrisy of the Bible-thumping zealots who would steal our freedoms away and impose by law their own brand of morality upon US citizens. I write because I have to. It has always been a hunger I must feed. I write because the best day of writing is always the best day of my life!

How does my Writing Process work?

I have always heard of binge eaters and binge drinkers; I am a binge writer. I develop an idea for a story or book. I note it in my journals and I write about the idea. I research and develop the characters. I read newspaper articles and interview people. At some point, the influx of information builds like water pressure behind a dam until I am forced to open the floodgates and release the weight of all that has accumulated. I have binges where I write every day, and during those times I commit to 500 words a day. Promising myself 500 words allows me to sit down when I have little time, and to get up when I simply must leave. But more often than not, 500 words become 1500 or even 2000. I endlessly revise, going back and rereading as often as I can. For instance, my current novel has had me researching Electric Shock Therapy Machines on the internet and trying to buy one on Amazon.com. I have interviewed a close friend of mine who ran river boats up and down the Mississippi and intra-coastal for thirty years. I am booking an evening ride on the Memphis Queen so I can approach President’s Island from the river, and I will also make a trip to the Island and hopefully spend some time exploring the Wildlife management Area that exists there within the city limits of Memphis. I have just begun the writing of the book, and the research will continue.

C.D.’s original post can be found at http://cdmitchell1964.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/my-writing-process-blog-tour/.

His whole blog can be found at http://cdmitchell1964.wordpress.com/.

Please visit his website at https://www.cdmitchell.net/.