…on Substack! Check it out and subscribe, won’t you?

Tag Archives: Movies

Brief Notes on Movies Vol. 1 No. 2

Sometimes Kalene and I spend so long trying to decide on which movie to watch that we run out of time for actual viewing. To combat this, I sought out several online lists of best/worst movies in different genres.

This comes from from a Rotten Tomatoes list of the best slasher films.

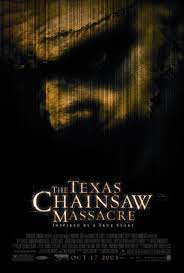

#94: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)

- Director: Marcus Nispel

- Starring: Jessica Biel, Jonathan Tucker, Andrew Bryniarski

- Had I seen it before? No, because like a lot of critics, I looked on this movie as unnecessary. Why remake a good movie without updating anything? It just seemed repetitive.

- Should it be on such a list? You know what? I’m okay with it. Yes, it remakes the original without doing something new to justify its existence, but the acting is a lot better than you often see in slasher films. The new death house is creepy, more in an typical-house-of-horrors way than in the original “inbred cannibal hicks with terrible taste in decorating” set design. Like the original, it feels brutal without actually showing all that much gore. The filmmakers miss the subtler (!!) aspects of Leatherface’s masks, but this doesn’t hurt much. Jessica Biel also isn’t required to scream nonstop for half an hour, which cuts down on the teeth-grating tension of the original, but I’m not complaining. One TCM using that many screams is fine. So were the critics right? Is this movie unnecessary? Yep, but it exists anyway, and unless you’re simply offended that anyone would remake the original, this one isn’t a bad watch.

There will be more installments in the future. Join me, won’t you?

In the meantime, buy my books. All the cool kids are doing it.

Got comments, questions, or complaints? Email me.

Brief Notes on Movies Vol. 1 No. 1

Sometimes Kalene and I spend so long trying to decide on which movie to watch that we run out of time for actual viewing. To combat this, I sought out several online lists of best/worst movies in different genres.

Here are some results from a Rotten Tomatoes list of the best slasher films.

#100: The Incubus (1981)

- Director: John Hough

- Starring: John Cassavetes, John Ireland, Kerrie Keane

- Had I seen it before? Not that I recall.

- Should it be on such a list? I’ll just say it wasn’t for me. It was nice to see John Cassavetes, but the acting, editing, and writing seem to match the movie’s RT “rotten” score. It would have been nice to see more of the subplots be resolved. Some of the minor characters don’t seem to justify their existence. Surely there are 100 better slasher movies.

#99: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022)

- Director: David Blue Garcia

- Starring: Sarah Yarkin, Elsie Fisher, Mark Burnham

- Had I seen it before? No.

- Should it be on such a list? I’m torn. The premise is a bit hard to believe; Leatherface has just been hanging around a deserted town all this time? In all that silence, nobody hears the screams of victims and the roaring chainsaw? On the other hand, the acting is often good, and the kills and scares often work well. I guess I can see why someone would put this on the list, but don’t come to the movie hoping to experience the same kind of visceral horror the first, less slick TCM gave us.

#98: A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989)

- Director: Stephen Hopkins

- Starring: Robert Englund, Lisa Wilcox, Kelly Jo Minter

- Had I seen it before: Yes, several times. We rewatched it a few months ago, so we didn’t revisit it in sequence with the list.

- Should it be on such a list? Let’s put it this way: If this one makes the top 100, then Elm Street #1-4 and New Nightmare better be on here, because all of them are better. Maddeningly, this one immediately erases most of the characters from #4, and apparently they couldn’t convince Patricia Arquette to return, which contributes to the less-than-stellar acting. By this time, Freddy is more comedian than monster, and we know better than to trust any ending that seems to leave him dead (again). I hate to say negative things about anyone else’s art, and Elm Street completists will want to take a look, but otherwise this is one of the weaker entries in the franchise.

#97: Madman (1981)

- Direction: Joe Giannone

- Starring: Gaylen Ross, Tony Nunziata, Harriett Bass

- Had I seen it before? No, unless my 1980s exploits erased it from my memory.

- Should it be on such a list? Look, I doubt anyone will argue that this film aspires to high art. Much of its execution will probably remind you of Friday the 13th and its various sequels: Boneheaded camp counselors wander into a supernatural killer’s woodsy territory, make the worst possible decisions, and get picked off one by one. That said, the film does give the titular madman a different backstory, including an evocation that echoes Bloody Mary and Candyman. The kills are mostly typical stuff, and you’ll probably wonder why there are seven or eight counselors for only five kids or so, but take my word for it; you’ve seen much worse acting. I do wish someone had told Giannone not to shoot so many takes that stretch out and out. Do we really need to pause for a full minute while a character looks around at nothing? Or follow someone across a large room as they shuffle inch by inch toward the next kill? No, we do not. Still, it’s fun in that cheap, amateurish way that provides much of the genre’s charm. I’m okay with its placement.

#96: Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood (1988)

- Director: John Carl Buechler

- Starring: Terry Kiser, Jennifer Banko, John Ortin

- Had I seen it before? Several times. We watched it again a couple of months ago, so we didn’t revisit it for this list.

- Should it be on such a list? I’m never sure why characters keep going back to Camp Crystal Lake. “Sure, the last six sets of counselors were brutally murdered, but I’m sure we’ll be fine.” This movie reflects the continuing shift away from counselors and toward residents of the lake area and/or those who show up specifically to find Jason Vorhees. That helps with the realism of a movie that otherwise nudges the human characters toward the supernatural, where Jason has already been living. Having said that, the storyline with Tina’s father makes little sense. I’m never sure why Tina’s mom trust Dr. Crews so much when he’s clearly shady. Not that any of this is supposed to matter. Jason is the real protagonist at this point. We’re mostly here for the kills. In any case, surely slasher writers and directors have produced enough quality work that the seventh installment of this franchise wouldn’t make the list. The movie isn’t offensively bad like the very worst films in history. It’s an acceptable movie if you realize ahead of time that you’ll need to grade on a sliding scale. Still, I was surprised it made this list.

#95: Halloween II (1981)

- Director: Rick Rosenthal

- Starring: Jamie Lee Curtis, Donald Pleasence, Charles Cyphers

- Had I seen it before? Lots of times. We watched it again a couple of months ago, so we didn’t revisit it for this list.

- Should it be on such a list? Yes. The film was written by franchise creator and original director John Carpenter and Debra Hill. It’s the last Halloween film to star Jamie Lee Curtis until her return several years later. The whole movie consists of Michael Myers stalking an injured Laurie Strode through a hospital and dispatching various medical personnel along the way. Of course, Donald Pleasence’s Dr. Loomis tries to stop him, leading to an explosive finale some of the subsequent movies basically ignore. The vicious-cat-and-mouse game doesn’t make for much of a story, but the cast elevates the material enough that I’m surprised the movie is this low on the list. Clearly a second-tier franchise entry that doesn’t have much in the way of character development, it’s still got enough going for it to justify your time.

There will be more installments in the future. Join me, won’t you?

In the meantime, buy my books. All the cool kids are doing it.

Got comments, questions, or complaints? Email me.

New Creative Nonfiction

My personal essay, “Dumbo and Me,” is now available at Literary Orphans. Check it out.

It’s a Moneyed Man’s World: Roma and Gender and Class Privilege

Alfonso Cuarón should make movies more often. Though his directing career began in 1983; even though his global profile grew exponentially with the release of Y Tu Mamá También, a Spanish-language film that also helped introduce world audiences to Gael Garcia Bernal and Diego Luna; despite his steady work as a writer, producer, and cinematographer, he has made only four feature-length films since 1998. Each is excellent: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, the first truly superb and perhaps strongest entry in that series; the dystopian thriller Children of Men; the Academy-Award-winning space-survival movie Gravity; and now Roma, his return to Spanish features and, perhaps, his most personal film to date.

Loosely based, allegedly, on Cuarón’s experiences as a child in early-1970s Mexico, Roma chronicles—to borrow Cheryl Strayed’s term—the ordinary miraculous in the life of Cleo, a maid in the household of a somewhat-prosperous family in Mexico City. The film begins with images of water splashing over and over across a stone-tiled floor. An open window, or perhaps a skylight, is reflected in the water, a square of brightness against the darker, dirtier stone, and through this not-quite-window, we see an airplane flying through an otherwise-empty sky. The motif of a single plane flying over Mexico repeats several times throughout the film, reminding us of a world beyond Cleo’s, of the possibility of escape, of both literal and figurative rising for those with means. As a domestic worker, though, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio, who manages to appear utterly unburnished and luminous at the same time) has no means. She lives with a second maid in a single-room apartment on the family’s property, always an exasperated shout away.

Viewers who value plot over character study may find Roma too slow, perhaps even plotless. One could view the film as a two-hour-plus slice-of-life story, wherein we learn that Cleo serves as a crutch for her sometimes-compassionate, sometimes-impatient employer, Senora Sofia. Except for one shocking scene in which a student protest is violently suppressed by government forces and an oceanfront sequence wherein a strong current endangers Cleo and two of Sofia’s children, not much “movie drama” happens. Cleo cleans up dog feces and makes tea. Cleo and fellow maid Adela go to the movies with their boyfriends. The kids wonder where their absent father is, and Sofia makes excuses for him. Groceries are bought. Beds are made.

Yet in representing the everyday reality of domestic workers and, more specifically, women, Cuarón turns the everyday drabness of Cleo’s existence into something more—a study in privilege and the complexities of professional domestic work.

In America, according to sources like The Huffington Post and Al-Jazeera, women comprise up to 95% of domestic workers, and the majority of those women are either immigrants or African-American. In 2019, those reports should surprise no one but the most clueless, white-privileged people among us. As in the old questions about who buries the undertaker or who cuts the barber’s hair, though, we might wonder who does domestic work for women of both color and means. In Roma, the answer seems to be other people of color, mostly women without means. It is difficult to watch the film without noting the class differences between Sofia’s family and Cleo. Sofia takes her children on several trips, where they and other families of their class drink and shoot guns and eat while poor women cook, clean, and watch the rambunctious children. When Cleo becomes pregnant by her boyfriend Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), she breaks the news during a make-out session in a movie theater. He excuses himself to buy refreshments and disappears. As Cleo sits alone and realizes he isn’t coming back, Cuarón holds the shot, forcing us to watch her nearly expressionless face and guess what she is feeling—sadness? Shock? Despair? Fear?

Luckily, in one of Sofia’s displays of compassion, she not only continues to employ the pregnant Cleo, but she also takes the young maid to a doctor and pays for the medical care. Yet, in other scenes involving Sofia’s unhappy marriage, she takes her anger and frustration out on Cleo, who has little choice but to take it. Where else would she go?

Not with Fermin. When Cleo eventually tracks him down, he denies paternity and calls her a “fucking servant,” though he lives in a hovel located in a neighborhood that makes Rio’s infamous City of God favela look upscale. He threatens to “beat the shit out of” Cleo and her “little one” if she ever accuses him of paternity again, exercising his male privilege of walking away from a pregnancy, leaving full responsibility to the woman. His disdain for her domestic work seems absurd, given that Fermin’s job, at that moment, seems to be undergoing bogus martial arts training, though his reasons for doing so later become heart-breakingly clear.

For all her class privilege, Sofia cannot escape the consequences of male privilege, either. After an early appearance in the film, her husband, a doctor, disappears, ostensibly on a research trip to Canada. In one remarkable moment outside the movie theater, though, we discover that, like Fermin, the doctor has used his male privilege to change his life, wife and children be damned. Sofia, like Cleo, is left to fend for herself.

Luckily, both Sofia and Cleo are more than capable. Though they can never truly bridge their class difference, they do form a sisterhood of sorts—two discarded women who work, nurture children, and strengthen familial bonds, not just surviving but, in their small and everyday manner, thriving.

In Roma, men wield most of the power, and women must negotiate the consequences of their whims. Educated women with money enjoy more choices than uneducated domestic workers. These power dynamics are never glossed over. Yet there is a kind of hope in the film—hope that, despite the sins of men and the upper classes, single working women of color can live lives of meaning and strength, even if their monetary situations make different meanings and different lives. The movie also reminds us that Cuarón is an artist we should treasure. Hopefully, we will not be forced to wait another five to seven years for his next feature.

New Movie Essay

Check out my latest essay for RoleReboot.org–“BlacKkKlansman and the American Past That’s Still Present.” What has(n’t) changed since the events in the film?

New Film Essay

Check out my latest at Role Reboot–“Why You Need to See the Mister Rogers Documentary”

http://www.rolereboot.org/culture-and-politics/details/2018-08-why-you-need-to-see-the-mister-rogers-documentary/

I’d Ask You to Think about Fish and Water: THE SHAPE OF WATER Review

Recently, I finally got around to watching Revolutionary Road, in which Michael Shannon plays a small but key role as a recently released mental patient who disrupts the marital façade of a suburban couple. Over the last several years, Shannon has proven himself an invaluable and versatile actor, in both film and on the television series Boardwalk Empire. His General Zod notwithstanding—a loud, overbearing performance that I blame more on the writers’ and director Zack Snyder’s fundamental misunderstanding of their source material—Shannon has done excellent work. He seems most at home playing edgy, borderline-insane authority figures. In Guillermo del Toro’s masterful, moving magical realist film, The Shape of Water, Shannon’s Richard Strickland is, in some respects, the straw that stirs the drink, so much so that I recently told my wife it might well be my worst nightmare to awake and find Shannon standing over me, watching me sleep with those bug eyes of his.

Except for the visually muddled destruction-porn mediocrity that was Pacific Rim—a movie that could have been Snyder’s work, except that it had some semblance of character development and a more-or-less coherent plot—I love del Toro’s work. Were I to rank his films, always a dicey and subjective and ultimately useless proposition, I would put The Shape of Water ahead of everything but Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone. It’s a strongly directed, well-edited movie with super makeup, beautiful retro set design, and a script that is equal parts Creature of the Black Lagoon monster-adventure and suspense-romance.

The plot: Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins), a mute cleaning woman at a research facility that looks like a dank VA hospital, lives a life of strict routine, right down to the perpetual tardiness that bemuses her best friend, Zelda Fuller (Octavia Spencer, who—in a situation that will likely please Academy voters even as it annoys cultural critics—plays a similar black-domestic role as her Oscar-winning turn in The Help). Each night, Elisa goes home to a small apartment located next to the near-identical residence of her other best friend, gay painter Giles (Richard Jenkins, who will also likely be recognized this award season).

Elisa’s dull life is disrupted with the arrival of Strickland and a mysterious research subject encased in a water tank. None of this affects Elisa much until, one day, an injured Strickland stumbles out of the lab, having gotten too close to whatever he brought into the facility. As the cleaning crew are left alone in the lab, Elisa discovers exactly what it is—a creature the film’s credits call Amphibian Man. He will look very familiar to fans of the old Warner Brothers Creature series. Played here by Doug Jones, who has made a career of embodying strange and/or homicidal humanoid creatures in del Toro films (see the Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth), the Amphibian immediately bonds with Elisa and demonstrates a human capacity to learn and communicate.

Many viewers’ experience with this film may hinge on how deeply they buy into the romance between Elisa and Amphibian Man, which includes not only an underwater sex scene but a later explanation of exactly how this kind of interspecies coupling is even possible, given the Ken-doll appearance of the Man’s bathing-suit area. Perhaps Elisa’s enchantment comes too easily. Perhaps we might wonder why and how the Man reciprocates her fascination, given the physical and communicative barriers between them. One answer is that Elisa finds ways to communicate sensually without a voice, through food and music. Another is that we are probably supposed to understand that these characters, voiceless and lonely as they are, thrive on empathy. A third reason is, perhaps, revealed in the (imagined?) final underwater scene, and while you may see the revelation coming, it still feels impactful.

The eccentricities of this love story should come as no surprise to del Toro devotees, nor should the excellent performances he coaxes from his cast. Hawkins’s expressive face and the timing and tenderness of her gestures could serve as an acting class in portraying emotion without words. Shannon, all self-righteous glower and rage, conveys the personal and the universal threat of a xenophobic government; it feels all too timely.

Spencer’s quiet strength radiates in her every scene; she makes Zelda’s roles as Elisa’s fierce protector, as wife of a no-account man, and as background player in a government facility oozing masculinity and classism, more than the sidekick-of-color comedy relief she might otherwise have been. The script helps, giving Zelda key roles in facilitating Elisa’s opportunities for romance and in the ultimate rebellion against Richard Strickland’s angry-white-male tyranny. Though this is primarily still a story about white characters, the occasional nod to the period’s racial injustices at least assure that those problems are not erased.

As Giles, Richard Jenkins, always a strong addition to any cast, delivers an award-worthy performance dripping with the loneliness of the outsider. A painter, a gay man who lives alone and wants desperately to find love, best friends with his mute neighbor and—using symbolism that is becoming more common—owner of a couple of cats (one of which is quite unfortunate), Giles steps out of his melancholy but entrenched life to help Elisa on her great adventure, and Jenkins makes Giles’s every moment, every decision, every out-of-character act both funny and uplifting.

Whether the film earns our understanding of Elisa and Amphibian Man’s romantic connection is a key question for viewers and critics, and my main quibble with the film is that it spends key screen time on a couple of scenes that seem to add little to the narrative or characterizations—Strickland at home, for instance. This time could have been used to deepen and broaden the connective tissue between Elisa and Amphibian Man. I was also a bit surprised at how Strickland’s story ends. Given what we learn about the nature and powers of Amphibian Man and how the movie generally rejects aggression as problem-solving, I expected something else. Still, as a writer, I know you have to tell the story inside you, and not every reader/viewer will applaud every narrative decision. Even so, my disagreements are relatively minor.

Overall, The Shape of Water deserves the critical love it has gotten since its release and makes a powerful addition to del Toro’s canon. I look forward to buying my copy.

B+

Suicide Squad and the Dangers of Critical Consensus

If the critics are to be believed, David Ayer’s 2016 film Suicide Squad represents one of cinema’s greatest failures in terms of artistic vision and commercial appeal. Its record-breaking opening and its 6.2-out-of-ten rating on IMDB (as of 19 September 2017) notwithstanding, moviegoers’ discourse about the film often mimics the film’s critical reception—a 40 out of 100 on Metacritic and a rather stunning 25% on Rotten Tomatoes. On the latter site’s sampling of critical quotes, we find gems such as the following:

- “To say that the movie loses the plot would not be strictly accurate, for that would imply that there was a plot to lose.”—Anthony Lane, The New Yorker

- “This is what happens when the comic book fanboys have taken over the asylum. It is damaged goods from the get-go, the kind of film grown in a petri dish in Hollywood.”— Colin Covert, Minneapolis Star Tribune

- “Sometimes it’s good to be bad. In Suicide Squad‘s case, bad is just plain bad. It gives villainy a bad name.”— Adam Graham, Detroit News

- “Suicide Squad had the potential to be an awesome superhero summer blockbuster, but feels more like a rushed unification of underwhelming action, a disappointing story, and stale character development.”—Chris Sawin, com

- “Taken from a popular DC comic series… helmed by a star quality director… peppered with a highly skilled, all-star cast … What could go wrong? Nearly everything.”—Leonard Maltin, Leonard Maltin’s Picks (All quotes taken from “Suicide Squad (2016), com)

To be sure, some of this criticism is warranted. When graded on the scale of truly great films to truly awful ones—say, Citizen Kane to The Room, or Casablanca to The Castle of Fu Manchu—Ayer’s movie falls squarely in the mediocre range. If we grade it on a sliding scale in which summer popcorn entertainment gets more of a pass for “not pretending to be any more than what it is,” the film scores a bit higher. Entertainment Weekly’s grade of B- (well above average, far from perfect) seems fairer than, say, Maltin’s claim that nearly everything goes wrong. Many things in the film go right, especially for its comics-fan target audience. Having read John Ostrander’s run on the comics title in the late 80s and early 90s, I felt more excited for this movie than I did for any other summer movie this year, even the superior Captain America: Civil War and the Ghostbusters reboot. This pre-fab investment in the film biases me; I probably came more prepared to like the movie more than the general audience or younger comics fans who have had less time to pine for an adaptation. It should therefore come as no surprise that I enjoyed Suicide Squad.

That does not mean that I am blind to its flaws, of which there are many. Nor am I taking issue with thoughtful critics who provide strong reasoning and textual evidence in their negative reviews. Honest, robust, and passionate criticism is essential to art and entertainment.

I admit to wishing, though, that so much of published criticism didn’t seem petty and mean-spirited, as if some critics are looking for any excuse to excoriate an artist’s work in snappy soundbites aimed more at entertaining than in improving the substance of the art. I am, in fact, unsure of how such criticism, masturbatory and self-important as it seems, differs from the very audience-baiting, cash-grab cynicism that these same critics often bemoan. An article written by Eve Peyser for Gizmodo is titled, “Suicide Squad Sets Box Office Record Because We Don’t Deserve Better Movies.” The only criticism of the film in this short post consists of linking to a Deadspin article about the movie and a claim that Suicide Squad is a “deeply mediocre film” (Peyser par. 2) Fair enough, but I would have been much more interested in reading Ms. Peyser’s thoughtful critique of the movie, rather than a simple statement that she hated it and that others probably did, too. Her thesis, as noted in the title, seems to be that we are to blame for bad movies because we keep paying to see them. That is an idea worth exploring, though to do so, we need to establish a commonly accepted definition of “bad movie” and prove that Suicide Squad fits the definition. Such an essay would require more time and space than was devoted to Peyser’s short post, but it would have been a much more interesting and substantive addition to our discourse about the film, its quality or lack thereof, and what our gravitating to it says about us.

To be clear, I am not taking issue with Peyser’s post, which also doesn’t pretend to be anything other than what it is—a short opinion piece making a provocative statement in order to increase site traffic and generate discussion about a major pop culture moment. What distresses me about American discourse on art and popular culture is that whenever critics overwhelmingly love or hate a film and then phrase their admiration or displeasure in language that is less than measured or thoughtful, their opinions take on the power of fact through sheer force. In simpler terms, once enough critics have passionately declared that Suicide Squad is bad, their opinions become our discourse. We all talk about the film as if it is factually bad to the extent that many fans and writers feel no need to justify their opinion—this in spite of the actual facts that critical consensus often changes over time and that one person’s waste of talent and budget is another person’s fun, thought-provoking entertainment.

The Big Lebowski was a critical and box office bomb, but it has since become a beloved touchstone for its own subculture, and not in the ironic, we’re-in-on-the-joke way that Plan 9 from Outer Space or The Room has become a cult favorite. Citizen Kane, often called the greatest film ever made, received mixed critical reviews upon its release. Conversely, Oscar winners like The English Patient and Crash have lost both critical and popular momentum over time. Donnie Darko has become a cult classic, even though it did woeful box office and puzzled many critics. Often, it is only with time and consideration that we can recognize a formerly overlooked classic or a work we initially rated too highly.

This phenomenon is not limited to cinema. Moby-Dick was a failure it its day and is now considered one of the great American novels. The most popular poets of the American nineteenth century have given way to Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. John Donne has gone in and out of style over the centuries. In spite of all this, we—both professional critics and audience members—often speak about a film as if its fate has been decided definitively, for all time. And for every thoughtful critic like a Leonard Maltin or Peter Travers or Lisa Schwarzbaum, there are a thousand trolls filling comments sections and Twitter feeds with recycled criticism and pure human ugliness instead of original thought.

For those who believe that Suicide Squad is flawed or just plain awful, all I ask is that you show your work. I ask the same of the film’s defenders. I ask that we wait until we experience a text for ourselves before we decide with whom we agree. And for the love of all that’s good and true, let us leave behind the flame wars and the name-calling and just talk to each other.

I’ll start. I’ve said that I enjoyed the movie as a biased comics fan, though I am not blind to its flaws. I loved the performances by Viola Davis, Margot Robbie, Jared Leto, Will Smith, and Jay Hernandez. Jai Courtney disappeared into his role of Captain Boomerang. I found the characterizations and development of Harley Quinn, El Diablo, and Deadshot to be intriguing and fun. The movie had the best soundtrack you could ask for, and many of the visual effects were strong. I appreciate Ayer’s decision to scrap King Shark for Killer Croc, a character who could be rendered by a living actor and makeup. And what we saw of Leto’s Joker whetted my appetite for more.

As for some flaws, here, in what I hope is conciliatory and thoughtful language, are some problems I had the picture. These points contain spoilers, so if you have not seen the film, beware.

- Other than the aforementioned Harley, Diablo, and Deadshot, most of the major characters were underdeveloped. Much of this problem can likely be attributed to having so many major players in one film—eight or nine Squad members, plus Rick Flag’s SEAL team, plus Amanda Waller and her flunkies, plus various military personnel and prison guards, plus the Joker and his henchmen. That’s a bunch, folks. This leads to several other problems, noted below.

- One major plot point we’re supposed to buy is that Rick Flag is in love with June Moone, a.k.a. the Enchantress, and his love for her is what keeps him under Waller’s thumb. However, we don’t see that love develop on screen, and the characters share so little screen time together that it’s tough to buy even after the fact. Ayer chooses to address this point by having Waller say, “We put the two of them together, and they fell in love just like we hoped, and now I own Flag.” The logic behind this plan makes no sense, and we are given nothing on which to base an investment in this relationship, even though many of the film’s attempts to connect with the audience’s emotions hinge on said investment.

- Speaking of Waller, those unfamiliar with the comics will likely find her to be, as Deadshot describes her, a gangsta, but as for her methods and motivation, we don’t have a clue. We know she’s worried about the threat of metahumans—that the “next Superman” will be a villain—but we have no idea why she believes that only other villains can fight such a threat. Perhaps we’re supposed to infer that she believes only bad guys can be controlled, but if so, this film’s plot pretty much scraps that notion, since the antagonist comes straight from the team itself. In fact, as the credits’ Easter Egg shows, she already had files on heroes—files that she gives to Bruce Wayne. If she knew of trustworthy good guys, why depend so much on bad ones that you have to threaten and bribe? Why couldn’t she try to form the Justice League, other than the fact that such an act would ruin the plot of the upcoming film?

- Killer Croc is given almost nothing to do until the end of the film and has no scenes that would require an actor of Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje’s caliber. He is unrecognizable under the makeup. Croc’s lack of both development and necessity makes the waste of a good actor almost as awful as what the film does with Adam Beach. It’s fine to kill a character to establish that, yes, the neck bombs keeping the Squad in line are real, and Waller or Flag are willing to use them. But why bother with hiring such a strong actor to do so little?

- Katana is criminally underdeveloped, which makes her big emotional scene fall flat. It’s hard to care about the fate of a character we have spent no time with and know very little about.

- Why does Deadshot almost never wear his trademark helmet and glowing eyepiece—except that it would rob us seeing Will Smith’s face?

- Much has been made of how the lead-up to the movie spent so much time on the Joker and Leto’s method-acting craziness, only to give us very little of what was shot. Even Leto has spoken out against how much of his performance ended up on the cutting room floor. I would not want to see the Joker overshadow the main storyline, but it seems unfair to both fans and Leto to give us so little footage, most of which is only marginally connected to the plot.

- Speaking of the plot, there are holes. Waller and Flag talk about how fighting the Enchantress’s transformed lackeys is useless, but then the Squad fights them and takes them out handily. What was Waller and Flag’s conversation based on, and why were they so wrong, and how did they feel about it? Why did June Moone bring forth the Enchantress in that hotel room, which allowed the villain to escape? Why does it take the Enchantress days to build her machine, and how is destroying military hardware the same thing as destroying all humanity? How does an ancient witch know how to make an intricate machine, anyway? Why didn’t Waller just have her retrieve all the secret information from every country instead of just Iran’s, and what were the generals going to do with that information? Why wasn’t the Enchantress’s big bad brother released at the same time she was? Flag kills the Enchantress by crushing her heart; why didn’t Waller do that in the first place, especially after just poking holes in it didn’t work? Why does Killer Croc never seem to get rattled? Why does finding out that Flag hid letters from his daughter cause Deadshot to complete the mission instead of just, you know, shooting Flag in the head? And so forth and so on.

- Sound editing—when the Enchantress is speaking English in the final scenes, I could barely understand a word she said. Since these are the climactic scenes, it seems kind of important.

- Many critics have said that the movie becomes too conventional in the last two acts. I think part of what they mean is that these unrepentant, scum-of-the-Earth bad guys start acting like good guys and doing good-guy stuff. The Captain Boomerang of the comics would never have come back to the team after being given an out; Jai Courtney’s character does, with no real explanation except that he’s apparently been affected by team spirit, the sense of which is then undercut when we learn that he is serving three consecutive life sentences and is therefore unlikely to get any benefits from his work. (For that matter, his trick boomerangs are so underused here that the audience might be forgiven for thinking they are ordinary.) Deadshot, Diablo, Harley, and even Captain Boomerang seem to form genuine bonds and become invested in each other’s fates, just as good guys would, even though they constantly talk about how awful they are. Complications and complexities are fine, even necessary and desirable, but you probably shouldn’t talk constantly about how you’re a vicious killer without a conscience and then undercut that concept with your every act. It would have been better if the Squad had continued as an anti-team, one that worked together out of mutual selfishness instead of an increasing sense of duty to each other. In the absence of that, what separates them from the Justice League, other than their criminal pasts?

- We are never really certain about the nature of the Enchantress’s henchmen—what they can do, why they look the way they do, what purpose they serve other than distraction.

- Why does the Joker look like a pimp?

Again, if you’re a comics fan, you might overlook some of these flaws. You know about Waller’s motivation and personality, and so when the film doesn’t show us, you can fill in the blanks yourself. As a stand-alone movie, though, Suicide Squad should have done better than that, especially since so many of the characters and events have been altered.

Given all of that, I can understand why many critics and viewers found the film to be mediocre or worse. And if you overlook the film’s flaws because all you want from it is to turn off your brain and go along for the ride, well, fine. What we should not do is let an apparent critical consensus at one moment in time take on the characteristics of fact, so that we ignore why a film might be good or bad and simply yell at each other about how good/bad it is. We cannot let unsupported statements of opinion stand in for substantive criticism. To do so teaches us nothing about the text or ourselves; it only widens the divide between camps, until, like the Suicide Squad itself often does, we turn our slings and arrows inward and leave each other bloody and battered but not enlightened.

Works Cited

Peyser, Eve. “Suicide Squad Sets Box Office Record Because We Don’t Deserve Better Movies.” Gizmodo.com, Gizmodo Media Group, 7 August 2016. http://io9.gizmodo.com/suicide-squad-sets-box-office-record-because-we-dont-de-1784950994. Accessed 28 November 2016.

“Suicide Squad (2016).” IMDB.com, IMDB, 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1386697/. Accessed 28 November 2016.

“Suicide Squad (2016).” RottenTomatoes.com, Fandango, 2016, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/suicide_squad_2016/. Accessed 28 November 2016.

“I Don’t Like Old Movies”–nonfiction #writing #nonfiction

Has Anybody Seen My Teeth?

2

“I Don’t Like Old Movies”

When you’re a teacher, sometimes nothing makes you feel older than your students.

Take the average college freshman. He or she is likely eighteen years old, the official age of adulthood as recognized by the United States military, legal system, voting booths, and so forth. When you reach that age, you assume all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities of adulthood—except, as my students would likely point out, in the eyes of parents who continue to treat them like kids and the local bars who won’t sell them a beer, even though they can fight in a war and be tried as an adult in a court of law.

Of course, many of these “adults” want all the privileges without any of the responsibilities, but putting that point aside, I face classrooms full of grown-ups every day, even at the lower levels of university education.

The problem? Given that it’s 2011 as of this writing, these students might have been born as late as 1993. How, in the name of all that’s holy, could that be possible?

In 1993, I was twenty-three years old. Even with a false start that put me behind by a year, I was only a couple of semesters away from earning my Bachelor’s degree. My daughter Shauna would turn four that year; my son Brendan would not be born for another two years, and Maya, bless her heart, would take another six. Kurt Cobain was still alive, and Seattle grunge ruled the music business. Some hair metal stalwarts kept on plugging, but those with rock-star fantasies had traded in their eyeliner and spandex for flannel shirts, dirty jeans, and cardigan sweaters.

These days, you can turn on certain classic rock radio stations and hear bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam. And when that happens, I always feel like someone has just stomped on the world’s brakes, the globe’s squealing tires nearly drowning out my cries of indignation. I mean, come on—the early 90s now qualify as “classic rock”? What acne-sprouting, voice-changing, wet-dream-having pubescent punk made that rule?

Me, I beg to differ. Kids—and if you’re under twenty-five, somebody still thinks you’re a kid, no matter how unfair it is or how loudly you protest—just because something’s older than you doesn’t mean it’s actually old. And even if it is old, it might not be bad.

Perhaps the disparity between what eighteen-year-olds think “old” means and what’s actually old becomes clearest in terms of their attitudes toward cinema. Plenty of exceptions exist, of course, but in general, people my students’ age seem to demonstrate a lot more patience with CGI-heavy trifles like Van Helsing and the Transformers franchise. And they seem much more willing to eschew minor considerations like a coherent plot, characterization and character development, editing, and understandable cinematography. If it blows up or flies into outer space and looks really pretty, younger folks seem to like it. Me, I want to know how the explosion fits into the story and how it deepens the plot or the character development. If it doesn’t do either, I don’t care what it looks like.

Beyond the special effects, though, many of my students seem to judge a film’s merit based solely on when it was released.

Not long ago, I was discussing the film Titanic in class when I realized that most of the students present that day were two or three years old during its theatrical run. Just a few years ago, Titanic was a cultural touchstone, a special effects triumph, a heart-breaking romance loved by people of all ages. Now, many of my students view it as quaint, a dismissible chick flick, a model of how things were done back in the old days. But at least they haven’t started calling it old…yet.

The Breakfast Club has not enjoyed such a kind fate. A couple of years back, I referenced it, likely to make some point about how it both perpetuates and critiques high school’s clique culture. Much like Glee, it utilizes stereotypes and archetypes of high school existence, sometimes for important cultural commentary, sometimes in ways that seem dangerous. But no one got my point; when I finished making it, I looked out into a sea of blank, bored faces, and realization dawned.

“None of you know what movie I’m talking about, do you?” I asked.

“Isn’t that the old movie about those kids in Saturday detention?” one student responded. He was the only one who even tried to join the conversation that had, unbeknownst to me, become a monologue.

“Old movie?” I said. “It came out in 1985!”

“Yeah,” somebody said. “Way before we were born.”

Wow, I thought. 1985 has somehow become ancient history, right up there with the Spanish Inquisition and the birth of Christ and the discovery of fire. If you watch 2001: A Space Odyssey closely, you might see John Hughes cavorting about the monolith with the rest of the knuckle-draggers. I suppose I’m probably there, too, but I’ve shaved since then.

I had long since gotten used to students’ rejection of movies made before they were born, but I admit that their attitudes about The Breakfast Club surprised me. It is, after all, a film about high school—the triumphs, the pain, the stupidity of some teachers and administrators, the way that parents just don’t understand. Having just come from high school, freshmen should have been able to relate. But because the movie came out way before they were born, they didn’t care. They weren’t even curious. So on that day, I learned that anytime I make a cultural reference, from any period, I have to explain it. I can’t assume they know anything about it, or that they want to.

I can also tell you that, if you grew up in the 1970s and found yourself afraid even to take a bath because of Jaws, don’t share that with kids today. They’ll laugh at you, as if the idea of a film’s having enough power to affect your real life is just plain silly. That’s a dumb movie, they say, because it’s old. That shark looks fake. It doesn’t compare to what a CGI tech could do. Never mind the courage and artistry it took to build a fake shark and dump it off the shore of Martha’s Vineyard. Never mind the deep emotional impact that the film had on a whole generation, the way that it basically invented the summer event movie, the cultural nerve it touched in terms of how we see sharks (hey, kids, what do you think we should thank for Shark Week?). That shark just doesn’t look right. It’s old, man. Watch Deep Blue Sea instead. Now that’s a classic.

I don’t know about you, but I remember when imagination trumped special effects every time—when the effects served to jumpstart your imagination, not replace it. By and large, though, my students don’t seem to get it. And so they dismiss Bruce the shark, and Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion genius, and the way that Charlie Chaplin somehow staged a cabin falling over a cliff. Sure, the cabin looks like a model, but we get the idea, right? And how did he manage to make that little figure jump out of the cabin right before it falls?

And, of course, Chaplin invokes the black and white era of filmmaking, from silent pictures up to the ubiquity of early color prints. Ask most of my students and any black and white film can be ignored; it’s simply too old to care about.

Such an attitude leads to a minor American tragedy, as a generation misses out on the great art and cool entertainment that came before. Instead, they have to discover it all later in life, even as hundreds of other films come out every year, leaving them only so much time to catch up. What will they miss because they think “older than me” equals “too old to matter”?

Of course, sometimes students just get it, like the recent freshman who admitted that Jaws ruined her beach vacation, or the one who ruefully confessed that Psycho scared her silly, so much so that she couldn’t finish watching it alone. On days like that, I smile a little wider and contemplate introducing them to Apocalypse Now, or Nashville, or Manhattan, or Scenes from a Marriage, or The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, or Night of the Hunter, or Bride of Frankenstein, or Citizen Kane, or Casablanca, or City Lights, or even Sixteen Candles. You know, one of those ancient, dusty movies that suck, that have nothing to do with today’s youth, that speak to no one but ancient, dusty people like teachers and parents who were never, ever kids themselves and can’t possibly understand why Transformers 3 represents American cinematic art at its finest.

On days like that, I dare to hope, and I feel a little younger, in spite of having been born before 1993.

Follow me on Twitter @brettwrites.

Email me at semioticconundrums@gmail.com.